Key findings for people born in countries where the main language is not English

The 2021 NCAS findings indicate that most people born in N-MESCs, like most Australians from all backgrounds, generally reject violence against women and gender inequality. However, the findings, like those for all Australians, also identify gaps in understanding and problematic attitudes in some areas.

Understandings of violence against women, such as the likelihood that it occurs in your own local area, the non-physical forms of violence and that men are more likely to commit domestic violence than women, could be improved.

Respondents born in N-MESCs were more likely to recognise that violence against women is a problem in Australia (82%) than to recognise that it is a problem in their own local area (40%). Similarly to the results for all Australians, this notable gap suggests that violence against women is seen as a problem that happens to other people, in other communities.

Respondents born in N-MESCs were also more likely to recognise physical (72–89%) than non-physical forms (57–68%) of domestic violence. This extended to forms of violence that are particularly relevant to the culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) community in Australia. For example, these include being forced to stop religious practices or being threatened with deportation by a partner (63% and 67% recognised these as forms of domestic violence, respectively).

There is also room for improvement in understanding the gendered nature of domestic violence among people born in N-MESCs. Half of respondents believed that domestic violence is equally committed by men and women (50%) despite global evidence that men are the main perpetrators and women the main victims of domestic violence. Further, a minority of respondents believed that men and women are equally likely to suffer physical harm (23%) or fear (32%) as a result of domestic violence.

Culturally and linguistically diverse women can be vulnerable to being misidentified as perpetrators of domestic violence. This misidentification may contribute to misperceptions that domestic violence is equally perpetrated by men and women.

Some sexist attitudes were strongly rejected, such as those that reinforce gender roles and stereotypes. However, there is still room for improvement across all aspects of attitudes towards gender inequality.

Gender inequality is still a pervasive issue in Australia. Problematic attitudes towards gender inequality include attitudes that deny the existence of gender inequality, limit women’s personal autonomy, normalise sexism, reinforce rigid gender roles and norms, and undermine women’s leadership. Gender inequality can intersect with racist attitudes and with systemic and structural inequalities related to racism to increase risk of violence against women from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Respondents born in N-MESCs broadly disagreed with many attitudes that support gender inequality. For example, most respondents born in N-MESCs “strongly disagreed” with attitudes that normalise sexism (59–89%), reinforce gender roles and stereotypes (53–75%) and undermine women’s leadership in public life (59–77%).

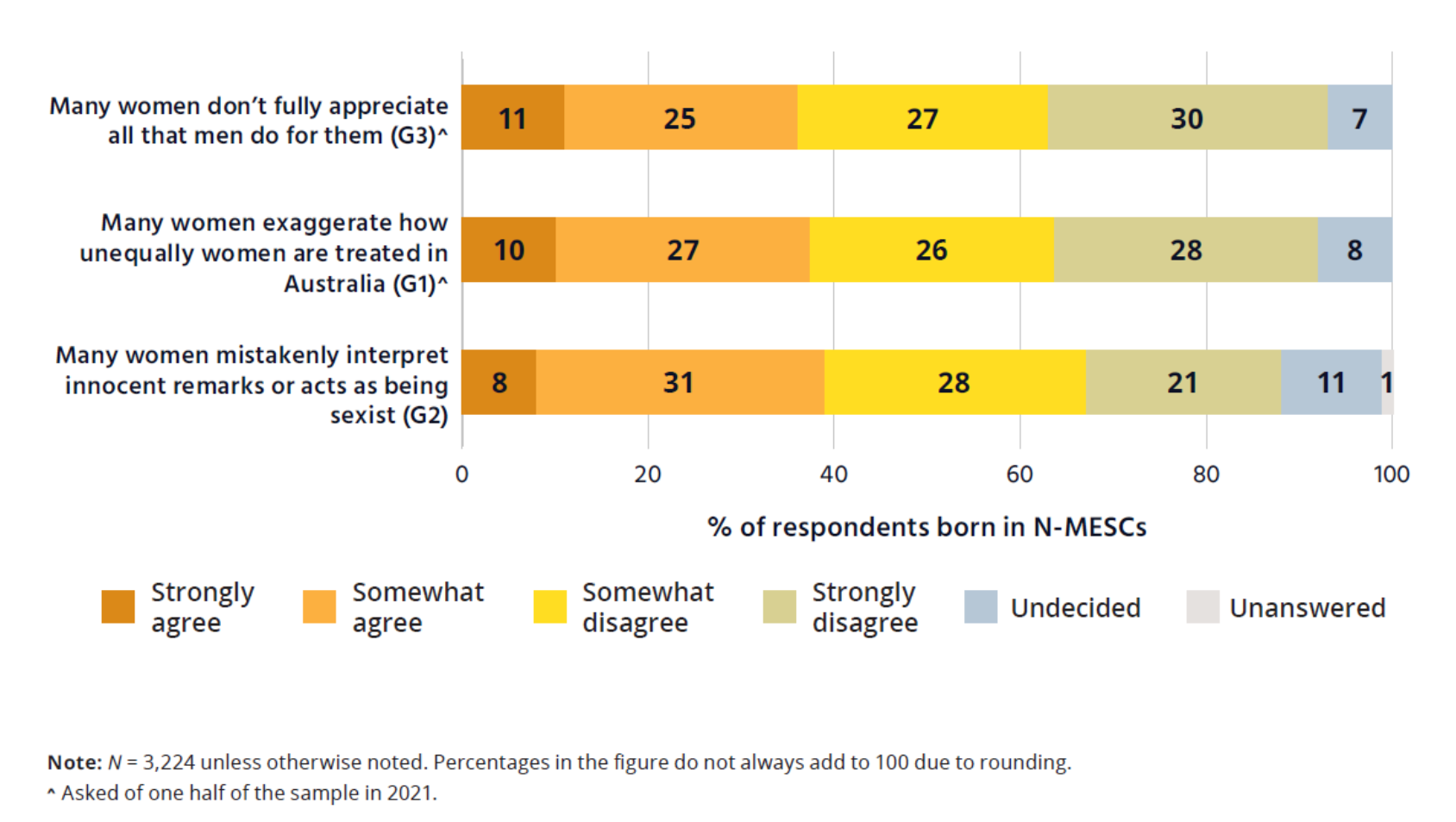

However, there is room for improvement. For example, fewer than half of respondents “strongly disagreed” with the following statements that limit women’s personal autonomy or deny gender inequality experiences:

- Women prefer a man to be in charge of the relationship (41%)

- Many women don’t fully appreciate all that men do for them (30%)

- Many women exaggerate how unequally women are treated in Australia (28%)

- Many women mistakenly interpret innocent remarks or acts as being sexist (21%).

Further improvements could be made to all types of attitudes towards gender inequality.

Attitudes that minimise violence or mistrust or objectify women are strongly rejected, but some respondents agreed with these damaging myths and stereotypes.

Many respondents born in N-MESCs strongly rejected attitudes associated with violence against women. Specifically, many “strongly disagreed” with attitudes that minimise violence against women (46–88%), objectify women and disregard their consent (50–83%), and mistrust women’s reports of violence (22–77%).

However, a concerning minority “agreed” (strongly or somewhat) with problematic attitudes that minimise violence (4–33%), mistrust women (8–40%) and objectify women (7–30%).

Problematic attitudes, including that domestic violence is a private issue and sexual harassment can be flattering, indicate a need for improving understandings and attitudes regarding all types of violence.

Many respondents born in N-MESCs recognised different types of violence and rejected problematic attitudes about domestic violence, sexual assault and harassment, technology-facilitated abuse, and stalking.

Domestic violence

Many respondents born in N-MESCs “strongly disagreed” with attitudes that blame victims and survivors for domestic violence (40–72%) and that normalise or excuse domestic violence (46–79%).

However, a sizeable minority of respondents born in N-MESCs endorsed some problematic attitudes towards violence against women. For example, some respondents “agreed” (strongly or somewhat) that domestic violence should be handled in the family (21%), that women are partially to blame if they stay in abusive relationships (40%) and that women going through custody battles often make up or exaggerate claims of domestic violence (37%).

These findings are important given the broader context that women from N-MESCs may experience difficulties separating or divorcing partners due to religious rules and cultural norms. For example, these difficulties include the perception of divorce as taboo and gender roles that pressure women to maintain family cohesion tolerate violence and remain in the abusive relationship. Women may also fear being ostracised from their community if they do not stay in the relationship.

Sexual assault

At least half of the respondents born in N-MESCs rejected attitudes that excuse sexual assault and “strongly disagreed” that a man was justified in forcing sex after a woman pushed him away (50–83%). However, they were less likely to “strongly disagree” if the woman had initiated kissing (50–60%) or if the couple was married (50–73%).

Most respondents born in N-MESCs (72%) recognised that it is a criminal offence for a man to have sex with his wife without her consent, but a concerning minority did not (16%) or were unsure (11%).

Problematic attitudes around consent were also borne out in small, albeit concerning minorities of respondents who agreed that “if a woman meets up with a man she met on a mobile dating app, she’s partly responsible” (15%) and that “if a woman is drunk and starts having sex with a man but then falls asleep, it is understandable if [sic] continues having sex with her anyway” (7%).

Sexual harassment

Most respondents born in N-MESCs “strongly disagreed” with problematic attitudes about sexual harassment (51–83%).

However, a minority “agreed” (strongly or somewhat) with myths that sexual harassment is flattering or not serious (9–18%), including that:

- women find it flattering to be persistently pursued even if they are not interested (18%)

- women should be flattered by wolf-whistles or cat-calls in public (14%)

- since some women are so sexual in public, it’s understandable that some men think they can touch women without permission (9%).

These types of attitudes are particularly concerning given the evidence that shows that sexual harassment is commonly experienced by migrant and refugee women in Australia, with almost half of all reported incidents occurring in workplaces.

These experiences are compounded by workplace policies and industry regulations that limit women’s options to choose other types of employment and leave them at risk of exploitation.

Technology-facilitated abuse

Most respondents born in N-MESCs recognised technology-facilitated abuse (62–67%) as “always” a form of violence and “strongly disagreed” with problematic attitudes towards this type of violence (59–75%). A small minority did not recognise some forms of technology-facilitated abuse and answered “no” when asked whether this was a form of violence against women, including:

- a man sending an unwanted picture of his genitals to a woman (8%)

- harassment via repeated emails and text messages (7%)

- abusive messages or comments targeted at women on social media (7%).

The majority of respondents recognised that it is a criminal offence to post or share a naked picture of an ex-partner on social media without their consent (91%).

Most respondents strongly disagreed with problematic attitudes that position women as responsible for technology-facilitated abuse that is perpetrated against them. For example, most respondents “strongly disagreed” with the belief that a woman is partly responsible:

- if her partner shares a naked picture without her permission (59%) or

- if a man she met on a dating app forces sex on her (75%).

However, a concerning minority “agreed” with these statements (29% and 15% respectively).

Improving the N-MESC community’s understanding of technology-facilitated abuse is important as emerging research suggests that CALD women may be one of the groups most at risk of this violence.

These women also face additional barriers to accessing support, such as having limited or no English-language skills. These barriers are heightened when women are isolated from social and familial networks and their abusive partners control or restrict their use of digital technologies.

Witnessing disrespect or abuse of women was concerning for most respondents. Respondents’ willingness to intervene depended on the context.

Most people born in N-MESCs said they would be bothered by witnessing disrespect or abuse of women (75–95%). However, their intention to intervene was dependent on the context in which the disrespect or abuse occurred. This context included the type of behaviour, presence of a power differential, anticipated peer support or criticism, barriers to intervention, and demographic factors as follows:

- Significantly more respondents would be bothered by witnessing verbal abuse (95%) compared to witnessing sexist jokes (75–89%).

- Respondents who were bothered by overhearing a sexist joke were less likely to speak up then and there if the joke was told by a boss (31%) than a work friend (48%).

- Most respondents who said that they would show disapproval when witnessing disrespect or abuse also thought that their friends would support them (67–68%).

- Most respondents who would be bothered but not intervene said they feared negative consequences (75–88%) or felt uncomfortable with speaking up (75–78%).

- Men born in N-MESCs (69–84%) were significantly less likely than women born in N-MESCs (81–94%) to report that they would be bothered by sexist jokes.

The findings of the Main report for all Australians similarly showed that large proportions of respondents who would be bothered but would not intervene when witnessing disrespect or abuse feared negative consequences (75–91%) or felt uncomfortable speaking up (75–79%).

Respondents’ attitudes towards violence against women were strongly related to their attitudes towards gender inequality.

The N-MESC respondents’ attitudes towards gender inequality explained 34 per cent of the variation in their attitudes towards violence against women. Understanding of violence against women explained 13 per cent of the variation in attitudes towards this violence.

These findings suggests that attitudes towards gender inequality and attitudes towards violence against women need to be addressed together, because they influence each other.

Understanding the relationship between the community’s attitudes towards gender inequality and violence against women is a pivotal step in identifying how we can improve and shift those attitudes and ultimately prevent the violence from being perpetrated.

There was a modest relationship between attitudes and certain demographic characteristics.

Demographic factors were modestly related to respondents’ attitudes towards violence against women. Overall, the demographic factors measured by the NCAS explained 18 per cent of the variation in attitudes towards violence against women.

The demographic factors most strongly related to attitudes towards violence against women were English proficiency (explaining 4% of the variation), formal education (2%), length of time in Australia (2%), age (1%), socioeconomic status of area (1%) and gender (1%).

The respondents born in N-MESCs who had higher rejection of violence against women were identified as belonging to one or more of the following groups: those who spoke English at home, had a university education, had lived in Australia for at least six years, were aged 16 to 24 and 25 to 34 years, lived in the highest socioeconomic areas, and/or were women.

Notably, some of these groups, in particular young people, do not hold much influence in their communities. Research has shown spiritual leaders are among the first individuals that migrant and refugee women disclose experiences of violence to.

At the same time, other research has shown that very few women disclose violence to religious leaders for fear that the disclosure would make the situation worse.

People from N-MESCs are a priority population for supporting improvements in understanding and attitudes towards violence against women.

When compared to respondents born in Australia, respondents born in N-MESCs had lower understanding of violence against women and lower rejection of problematic attitudes towards gender inequality and violence.

Based on these findings and broader research about barriers that women from N-MESCs face in getting help for domestic violence situations, people from N-MESCs are a priority population for supporting improvements in understanding and attitudes towards violence against women.

However, it is important to recognise that there is still substantial work to be done to improve community understanding and attitudes regarding violence against women and gender inequality for all Australians.

Only one fifth to a half of respondents born in N-MESCs, MESCs, and Australia met the aspirational goal of “advanced” understanding and attitudes.