Key findings for young Australians

Trends in attitudes and understanding show improvement

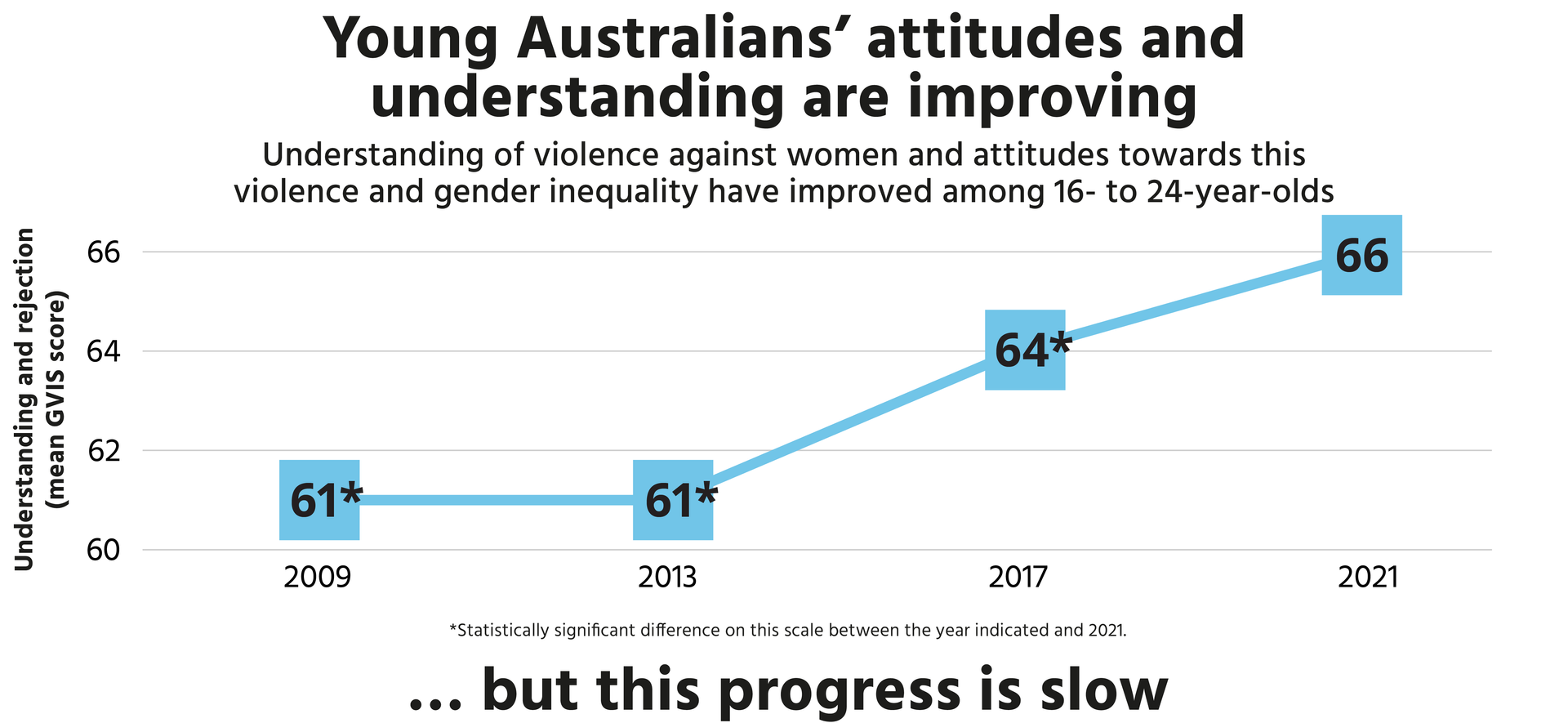

Many of the 2021 NCAS findings for young people were similar to those for all respondents, as seen in the Main report, and respondents aged 25 years or older. Similar to all respondents, young respondents demonstrated slow but positive shifts over time in understanding of violence against women and improvements in attitudes towards this violence and towards gender inequality.

Young people showed significant improvement in 2021 for all understandings and attitudes measured by the NCAS compared to one or more previous years (2017, 2013 or 2009). Between 2017 and 2021 specifically, young people’s understanding of violence against women, rejection of gender inequality, rejection of violence against women and rejection of sexual violence significantly improved. However, attitudes towards domestic violence plateaued between 2017 and 2021, despite improvements over the longer term.

These trends were also seen for all Australians, as seen in the Main report, except that all Australians did not demonstrate a significant increase in rejection of violence against women between 2017 and 2021.

A minority of young people (27–43%) demonstrated “advanced” understanding of violence against women, rejection of gender inequality, rejection of violence against women, and understanding and rejection of technology-facilitated abuse. These findings indicate that most young people could still improve their understanding and attitudes.

Gender differences in attitudes and understanding persist

The 2021 NCAS highlighted a statistically significant gender gap in young people’s attitudes and understanding, with young men consistently lagging behind young women. Occasionally, young men also lagged behind young non-binary respondents (although the small number of young non-binary respondents reduced the ability to conduct some comparisons and to detect significant differences involving this group).

For example:

- Young men’s understanding of violence against women, rejection of gender inequality, rejection of violence against women and intention to intervene prosocially when witnessing violence or abuse were not as developed as those of young women.

- Young men lagged behind young non-binary respondents in their rejection of gender inequality and rejection of some aspects of violence against women.

In 2021 young men and young women had similar levels of understanding of the gendered nature of domestic violence as perpetrated mainly by men against women, with women more likely to experience fear or physical harm as a result. However, young men and young women both demonstrated a decline since 2013 in understanding of the gendered nature of domestic violence.

Understanding of violence against women varies by age and type of violence

Young people are still developing their understanding of violence against women. Overall, young respondents were significantly less likely to have an “advanced” understanding of violence against women compared to people aged 25 years or older. For example, young people were:

- significantly more likely to think that men and women experience fear equally as a result of domestic violence

- significantly less likely to recognise technology-facilitated abuse as a type of violence against women.

Young people recognised that domestic violence and violence against women can include a range of physical and non-physical behaviours. However, they were more likely to recognise physical behaviours as violence compared to non-physical behaviours, including those that involve exploitation of aspects of a partner’s identity or experience (e.g. their gender identity, disability, visa status etc.).

In 2021 compared to both 2009 and 2013, young people had a lower understanding that domestic violence is gendered, with men being the main perpetrators and women being the most likely to suffer physical harm as a result.

Young people were more likely to recognise that violence against women is a problem in Australia (91% agreed) than in their own local area (53% agreed). However, compared to respondents aged 25 years or older, young people had a higher understanding that violence against women occurs in their own suburb or town.

Young people were significantly more likely than respondents aged 25 or older to agree (“somewhat” or “strongly”) that they knew where to get support for someone experiencing domestic violence.

Attitudes towards gender inequality develop early

Attitudes towards gender inequality were similar for 16- to 17-year-olds, 18- to 24-year-olds and respondents aged 25 years or older, suggesting that attitudes towards gender inequality are formed early.

The exception to this was that younger respondents were less likely to reject some problematic gender norms that limit women’s autonomy in relationships. Rejection of some norms limiting women’s autonomy was lower for 16- to 17-year-olds compared to 18- to 24-year-olds, and also for young people (16 to 24 years) compared to respondents aged 25 years or older.

Compared to respondents aged 25 years or older, young people were significantly less likely to “strongly disagree” that women prefer men to be in charge in relationships or that jokes about being violent towards women are okay. However, young people were more likely than those aged 25 years or older to “strongly disagree” with the notion that women need children to be fulfilled.

Some but not all attitudes towards gender inequality are improving

While attitudes towards gender inequality appear to form early, comparing young people in 2021 to young people in 2017 revealed some improvements in attitudes towards gender inequality.

Similar to all respondents, young people in 2021 showed significantly improved rejection of attitudes that reinforce gender roles, deny inequality and normalise sexism.

During this period, however, young people, like all respondents, did not show significant improvement in attitudes that undermine women’s leadership. Young people also showed no significant improvement in rejection of problematic attitudes that condone limiting women’s autonomy in relationships, whereas all respondents did show significant improvement.

Attitudes towards violence against women are improving and continue to develop with age

Young people demonstrated some progress in their attitudes towards violence against women. Between 2017 and 2021, young people significantly improved their rejection of attitudes that condone violence against women, whereas this rejection plateaued for all respondents as seen in the Main report).

Rejection of problematic attitudes towards violence against women was often stronger for young people aged 18 to 24 years compared to those aged 16 to 17 years. This finding suggests that youth is a period within which attitudes towards violence against women are noticeably changing.

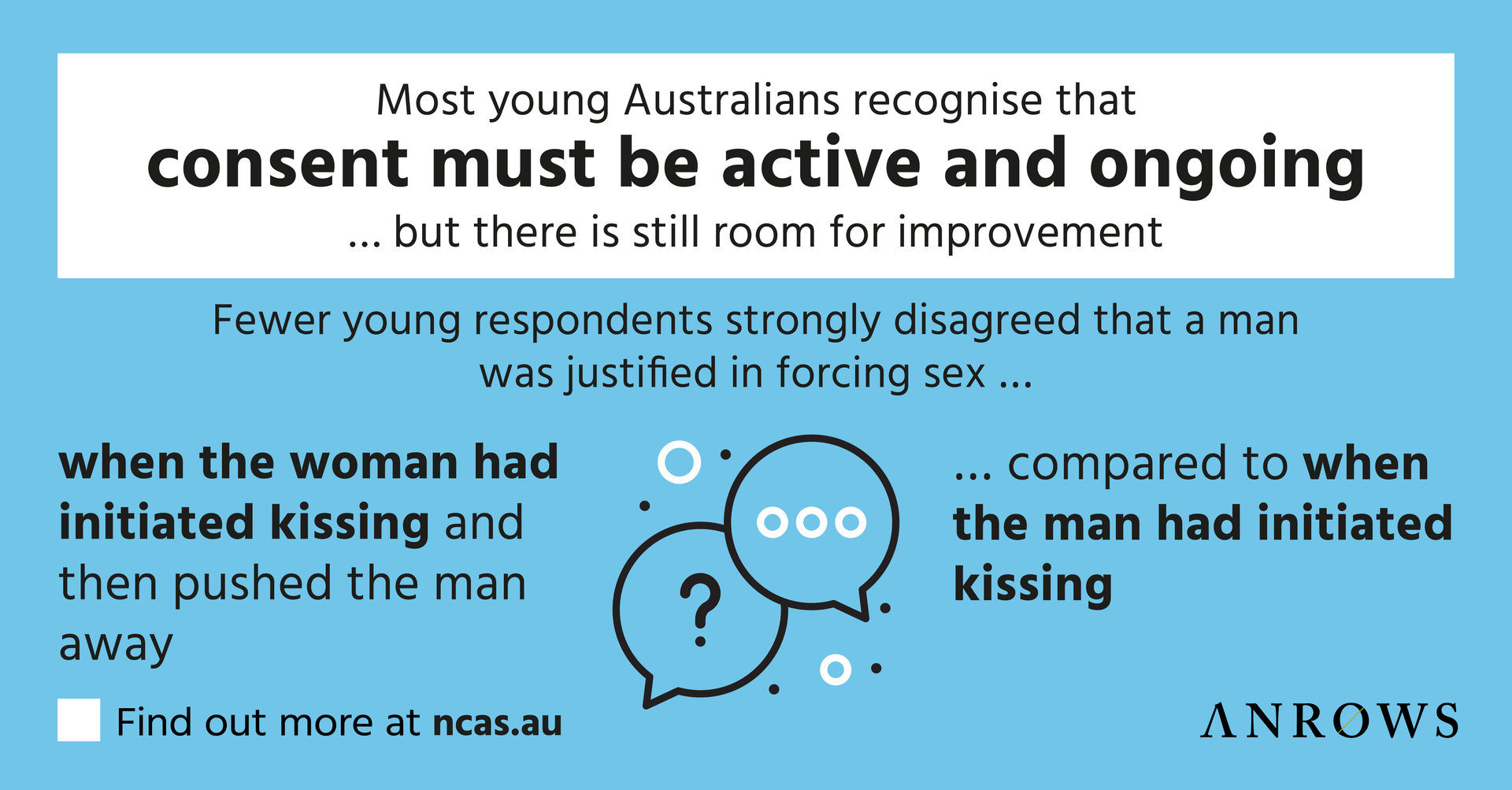

Young people demonstrate nuance and uncertainty about sexual consent and objectification of women

Young people expressed nuance and uncertainty in their attitudes in some areas. Some of this uncertainty focused on sexual violence and occasionally on intoxication. While young people significantly increased their rejection of sexual violence between 2017 and 2021, a concerning minority still held problematic attitudes that excuse rape, particularly in scenarios where the woman had initially shown interest in sex.

Young people’s attitudes towards sexual violence involving alcohol or drugs also depended on whether it was the victim or perpetrator who was intoxicated. When compared to those aged 25 years or older, young people were significantly:

- more likely to excuse the perpetrator if he was drunk or affected by drugs

- less likely to excuse the perpetrator if the victim was drunk and fell asleep.

Young people were significantly more likely than respondents aged 25 years or older to “strongly disagree” with some attitudes that objectify women, including beliefs that women should be flattered by wolf-whistles or cat-calls and that it is understandable for a man to continue having sex with a drunk women who falls asleep.

A minority of young people also agreed with the rape myth that sexual assault is mostly committed by strangers.

Mistrust of women and minimisation of violence persists

Young people’s rejection of attitudes that mistrust women’s reports of violence and those that minimise violence is still developing. Developments between 2017 and 2021 included a significant increase in young people’s rejection of attitudes that:

- mistrust women’s reports of violence

- objectify women and disregard their consent.

Young people’s rejection of attitudes that minimise violence has also significantly improved over the long term, although this improvement stalled between 2017 and 2021.

In 2021, a minority of young people agreed with stereotypes of women as vengeful and untrustworthy, and attitudes that perpetrators are less responsible if under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Such attitudes demonstrate mistrust in women’s reports of violence and minimise violence or shift blame from the perpetrator to the victim or survivor.

Young people had significantly weaker rejection of problematic attitudes that excuse and minimise violence compared to people aged 25 years or older. For example, they were significantly less likely to “strongly disagree” with beliefs that domestic violence can be excused if the perpetrator was drunk or later regrets their behaviour, and attitudes that domestic violence is a private matter that should be handled within the family.

Bystander responses depend on context

While most young people expressed the intention to intervene prosocially when witnessing abuse or disrespect against women, this depended on the context, the type of behaviour and the presence of power differentials.

Young people were significantly more likely than those aged 25 years or older to be bothered by sexist jokes in the workplace but were significantly less likely to intervene if bothered by a sexist joke told by a boss.

Young people were also significantly more likely to be bothered by, and to say they would intervene if they witnessed, verbal abuse compared to a sexist joke.

Promisingly, most young people thought that their peers would support them either publicly or privately if they intervened.